Introduction

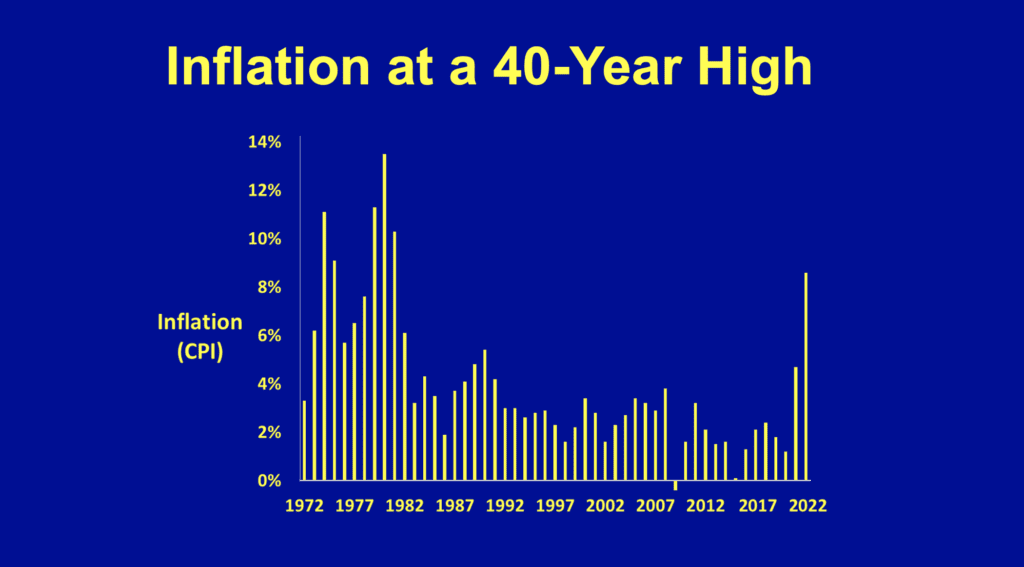

With inflation under 3% for most of the last few decades, most forward buying (also called investment buying) by wholesalers and retailers has in recent times been in response to promotional discounts offered by manufacturers. But with inflation surging in the last couple years, buyers are increasingly engaging in forward buying to lock in lower prices before announced or anticipated price increases. This includes stocking up on goods before new tariffs go into effect, which has been increasingly common since 2018. With the right approach to determining how much volume to purchase, buyers can significantly increase their company’s bottom line.

Background on Forward Buying

For the purposes of this article, I’m defining forward buying, also known as investment buying, as any increase in purchase quantity to take advantage of favorable pricing before a promotion ends or before announced or anticipated price and tariff increases go into effect. Companies store the resulting inventory for future resale, or in some cases engage in diverting, the resale of inventory to other channels or regions. Anecdotal evidence suggests that some companies earn as much as 30% of their overall profits from forward buying activities.

Trade promotion discounts are usually intended to fund consumer price reductions, feature ads, and store displays, but wholesalers and retailers can often buy much more than needed for the consumer promotion and pocket much of the savings themselves. In recent years, manufacturers have increasingly curtailed such behavior by enforcing the requirement to pass on savings to the consumer using point of sale scanner and loyalty card data, or by adopting EDLP (everyday low pricing) strategies.

Now, facing significant inflation and increased tariff activity, wholesalers and retailers have a new motivation to engage in forward buying. When manufacturers announce upcoming price increases, typically a few weeks to several months in advance, buyers may find it advantageous to stock up on inventory before price increases occur. The same is true for scheduled tariff increases, which are spelled out in laws well in advance. Buyers may even act on the anticipation of price increases, though this involves taking a speculative risk on the amount and timing of such increases.

Even if price increases are announced in advance, forward buying incurs risk, because you don’t know how quickly you will be able to sell the increased levels of inventory. And if market demand changes, you may be stuck with a lot of inventory you will have to sell at fire sale prices, or write-off entirely. In addition, retailers and cash and carry wholesalers expose themselves to an entirely new form of risk when they engage in forward buying. Typically, these businesses can resell merchandise and collect cash before they have to pay their suppliers, eliminating the need to increase working capital. But when they engage in forward buying, they must increase working capital and potentially face a cash shortage if they can’t resell the inventory fast enough.

Determining the Optimal Forward Buying Quantity with Inflation

When pricing is not a factor, buyers usually settle on a regular pattern of buying, typically topping up their inventory at a regular interval or ordering a standard replenishment quantity whenever their stock levels hit a predetermined reorder point. These approaches yield the familiar sawtooth pattern of inventory levels over time. In determining the quantity and timing of ordering, buyers are making a tradeoff between ordering costs and inventory carrying costs. Order too often, and you will incur high order handling costs. Order too seldom, and you will have to order large quantities and incur high carrying costs. The ideal quantity is the so-called economic order quantity.

Determining the ideal ordering pattern is not trivial, but once it’s done, you can leave it as is, at least as long as the various inputs stay the same (e.g., carrying costs, supplier lead times, etc.). When you are presented with a forward buying opportunity, you must factor in the potential savings from buying at a discount (or locking in a lower price). These savings will offset higher carrying costs and increase the optimal purchase quantity. The calculation is a bit more complicated, and you must redo the calculation every time you are presented with a forward buying opportunity.

When faced with a special deal or upcoming price increase, your goal is to figure out how much to buy. Let’s say you normally top up your inventory every week, and now the price is going to increase by 20% in two weeks. If you continue to place your normal weekly order, you will miss an opportunity for additional profit. You can forward buy several weeks’ worth, but at some point, the incremental carrying costs of holding inventory an extra week will outweigh the increased margin from getting the lower price. You should buy a quantity that gets you to this point; anymore and your gains will start to decline.

Below are some of the key inputs and considerations you must take into account to make this calculation:

- Inventory Carrying Cost: This will typically come from your finance department and is expressed as a percent of inventory value per time period, e.g., 30% per year. It should include your cost of capital, cost of warehouse space and handling, and the anticipated cost of shrink from expiration, damage, theft, etc.

- Forecast Demand: This should come from your demand planning system, and should be your actual forecast demand (typically by week), not your historic or average demand. A lot of buyers just use the average demand for the last few weeks, but if you have a good demand planning process, you should use the forecast, because that’s going to be a better predictor of how fast you will consume the inventory and thus how much you should stockpile.

- Order Handling Cost: This typically comes from your procurement department and should reflect fully loaded costs to place, track, receive, and settle payment for an inbound order.

- Borrowing Cost: This is your interest rate to borrow money to finance forward buying, a common practice among wholesalers and retailers. Interest rates will of course increase as inflation increases.

- Anticipated Price Change: Here’s where discounts, inflation and tariffs come in. In the case of inflation, you will of course need to use the specific announced or anticipated price changes for each product, rather than any broad-based inflation rate.

- Expiration Date: Any forward buying needs to take into account product shelf-life for perishable products such as groceries and pharmaceuticals, so you don’t stock up on goods that will expire before you can sell them and need to be sold on the cheap or disposed of. Likewise, you should consider the effective “expiration date” for any product category that will lose value rapidly over time, such as electronics (because of product obsolescence) and apparel (because of changing seasons and fashions).

- Truckload/Container Quantities and Associated Discounts: When dealing with product categories for which you benefit from transportation discounts for full truckload quantities, you’ll want to factor this in to your forward buying decisions and typically buy in multiples of truckloads. For each product category you’ll need to take into account weight, cube, pallet, and case capacity constraints.

- Supplier Cumulative Discounts: If you are offered a special deal from an alternate source, you need to consider the fact that while a such a deal may sound attractive, any shift of volume to this alternate supplier could affect cumulative volume discounts you receive from your regular suppliers. For instance, a regular supplier might give you a 10% discount if your annual volume exceeds 100,000 cases, and you wouldn’t want to risk not hitting that discount tier because you bought products from another supplier.

Do the Math … But not in a Spreadsheet

Traditionally, buyers have evaluated individual deals using rules of thumb or spreadsheet calculations. In this day and age, there’s no excuse for relying on rules of thumb – the calculations are not rocket science, and if you use rules of thumb, you are going to leave money on the table (or worse, get stuck with too much inventory).

The calculations required to optimize purchase quantities are certainly possible in a spreadsheet, but there are a few problems with the spreadsheet approach:

- Spreadsheets are error prone. When you are making a decision on whether to buy an additional $50,000 of inventory on a purchase, you need to get it right. There’s too great a risk you will make a mistake using a spreadsheet.

- Spreadsheet calculations are not standardized. When evaluating forward buying opportunities, you want a standardized calculation, blessed by your finance department, that everyone is using consistently. The decision on whether or not to take advantage of a deal should not depend on who is doing the evaluating, but should be based on a single, best answer based on your corporate-wide evaluation criteria.

- Spreadsheets are not integrated into your day to day replenishment planning process. You are going to want to decide how much to buy in the context of your overall replenishment planning process. This is because the relevant data will be in your planning system, and you need to evaluate the incremental profit opportunity in the context of your regular replenishment needs.

- Spreadsheets are too slow. As I said, the calculation is not rocket science, and a spreadsheet can certainly process the calculation quickly. But if you have to manually enter evaluation criteria in a spreadsheet and fiddle with the data and calculations, you may lose out on forward buying opportunities to a competitor who can act more quickly. Such a lost opportunity could be in the form of a special clearance deal offered on the phone, “while supplies last.” It could even be a deal presented by a planned price increase, if supply is limited and competitors race to vacuum up all available cases as fast as they can.

These calculations are best done in your enterprise supply chain system, where you can standardize on an approach, factor in your replenishment requirements, and quickly make decisions to take advantage of forward buying opportunities. For this reason, we incorporate forward buying functionality into our Buyers Workbench application.

Conclusion: Leverage the Silver Lining of Forward Buying in Today’s Climate of Inflation

Inflation and tariffs have created a challenging climate. But wholesalers and retailers can reduce their impact by taking advantage of the new opportunities presented by forward buying. By quickly and accurately evaluating opportunities, buyers can make smarter buys and increase profits – and discover a silver lining to the cloud of increased inflation and tariffs.

To Learn More

If you’d like to discuss how New Horizon can help you with your forward buying strategy, please contact us – we’d love to talk.